La Salle University

Social work grads share experiences from the frontline

Graduates of La Salle’s Bachelor of Social Work program provide vital support in the fight against COVID-19.

Medical professionals have adopted an all-hands-on-deck approach to battle the coronavirus pandemic, and social workers have been right there on the frontline—providing vital support for doctors, nurses, patients, and families in the fight against COVID-19.

The public at large traditionally has viewed social workers as advocates for vulnerable children. That understanding of the profession overlooks many of the crucial services social workers provide, like addiction and relationship counseling, housing and financial assistance, job training, and now, much-needed assistance to combat a pandemic.

As 2020 has shown, there is no such thing as a cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all career in social work.

“Social workers have the skills to help bridge differences and advocate for individual, family, and community well-being,” said Janine Mariscotti, MSW, LCSW, assistant professor and graduate program director of social work at La Salle University. “During this dual pandemic of COVID-19 and racism, social workers are at the forefront of addressing the issues and challenges of our time in a variety of settings.”

La Salle has furthered its commitment to positioning students for success in social work careers by introducing a new Master of Social Work (MSW) program. The program will be available in part- and full-time tracks, and qualifies graduates to become title-protected, professional social workers eligible to earn licensure across the country, where their services are needed now more than ever.

“They are on the frontline working with people as they face the devastation COVID-19 brings to their families and their well-being,” said Rosemary Barbera, Ph.D., associate professor, department chair, and undergraduate program director of social work at La Salle. “They are helping families in a variety of settings using many different approaches.”

Graduates of La Salle’s social work program recently shared their experiences from the frontline, where they are being asked to do whatever it takes to help fight COVID-19.

Julia Hartman, ’10

Julia Hartman, ’10

Emergency department social worker

Good Samaritan Hospital, Los Angeles

“We’re seeing a lot more people in full cardiac arrest coming in and a lot of people are involved. Before, I’d stand back. Now, I’m right there asking, ‘What does the doctor need?’ I’m doing whatever I can, even if that means getting supplies or tying up gowns or scrubs for people. My immediate goal is looking for family. The moment (patients) are brought in, I’m running out to the ambulance trying to get the phone number that called 911, trying to figure out if they are family. I’m trying to get someone to the hospital as soon as possible, or talk to (the patient) if we have to intubate them. And with homeless individuals, sometimes you can’t track down family. The department of health will call me for contact tracing, asking ‘Do you know so and so? Do you have any information on them?’ and I’ll tell them we have no idea who they are. They’re basically Jane Does.”

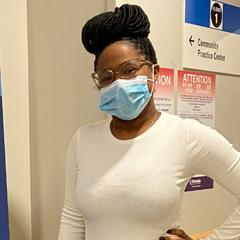

Emmanuella Theophile, ’13

Emmanuella Theophile, ’13

Outpatient pediatric social worker

Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia

“There have been times when we’ve been so short-staffed due to people being out sick or quarantining that I’ve jumped into the front desk role to check patients in and out. I help put the patients in the treatment room and do the COVID screening. Working throughout COVID, you can’t just look at things like, ‘I’m just a social worker, that’s my role.’ I believe strongly in learning as much as I can wherever I work, because you just never know where it will take you. Just look at what’s been required of (social workers) this year.”

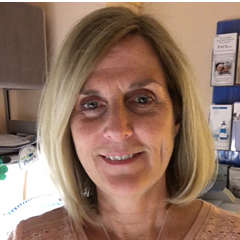

Mary Oleksiak, ’81

Mary Oleksiak, ’81

Outpatient oncology social worker

Abington Hospital Jefferson Health, Abington, Pa.

“We are trying to support both our immune-suppressed patients, who are very fearful of COVID, as well as our staff. I have been part of a proactive support team for staff. More than anyone, this has impacted the nurses because they’re the ones who have the most direct contact with patients. It’s been a stressful time for them and our radiation therapists, who also have direct contact. We make rounds on a weekly basis and let them know we’re here to help them support patients. We discuss how to talk to their kids about what they’ve been dealing with, because kids have so many questions. We help them destress, with exercises either in the middle of their day or in the car on the way home before they walk in the house. That’s another stressful time because you’re worried about bringing germs home.”

Noheli Taveras, ’13

Noheli Taveras, ’13

Social worker

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia

“I called all the funeral homes in the city because I wanted to understand what the protocols were regarding COVID patients. Were they accepting COVID patients? Were they allowing funerals or viewings or anything of that sort? Was there an additional cost? Were they accepting COVID patients that were under the Medicaid grant? Families had so much to deal with already, how could they stay on top of this, too? So that loved ones knew what to do, I took all the information and sent it to everyone on staff, and to HUP (the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania) and Pennsylvania Hospital, as well.”

Victoria (Tory) Tuman, ’13

Victoria (Tory) Tuman, ’13

Supervisor of behavioral health

Temple University Hospital Episcopal Campus, Philadelphia

“I’ve worn a lot of hats this year. It’s a mentality of ‘Whatever needs to get done, jump in to do it.’ We had iPads donated for our behavioral health patients. I used them to help facilitate family meetings and educate our staff on setting up things like Microsoft Teams and Zoom calls. I’ve kind of become the IT department. We got new chairs for one room and I was in the loading dock moving the chairs around. I helped patients vote (in the November election). You’re everyone’s personal assistant, whether it’s the patients, the families, the doctors, or the nurses. We try to do it all for them.”

—Patrick Berkery