A University-sponsored teach-in showcased the success of a Colombian program that is building peace through education and agriculture.

From personal experience, Edgar Calderon knows just how difficult it is to elevate yourself and your family from poverty in the more rural and remote areas of Colombia. He grew up in a town affected by drug trafficking and guerilla violence. Opportunity there is scarce—whether it’s opportunity to receive a quality education or opportunity to secure decent work.

“Among young people,” Calderon said, “the only way to succeed in life with guns. The life of trafficking is attractive and appealing.”

Access to education in Calderon’s town, and many others like it, is absent. Many of Calderon’s friends, he said, ended up either imprisoned or murdered.

How did Calderon escape a similar fate? A parish priest encouraged him to apply for a program called Utopia, offered at Universidad de La Salle of Bogotá’s rural campus in Yopal, Colombia.

Calderon shared stories from his time in the program, what he called “a life-changing experience,” during an hour-long teach-in offered by La Salle University as part of its commitment to educate for peace and solidarity. La Salle organized the Oct. 6 event, sponsored by the Office of Mission, Diversity, and Inclusion, and promoted globally as part of International Lasallian Days for Peace, running from Sept. 21–Oct. 21. Guests, panelists, and participants of the event spanned three continents.

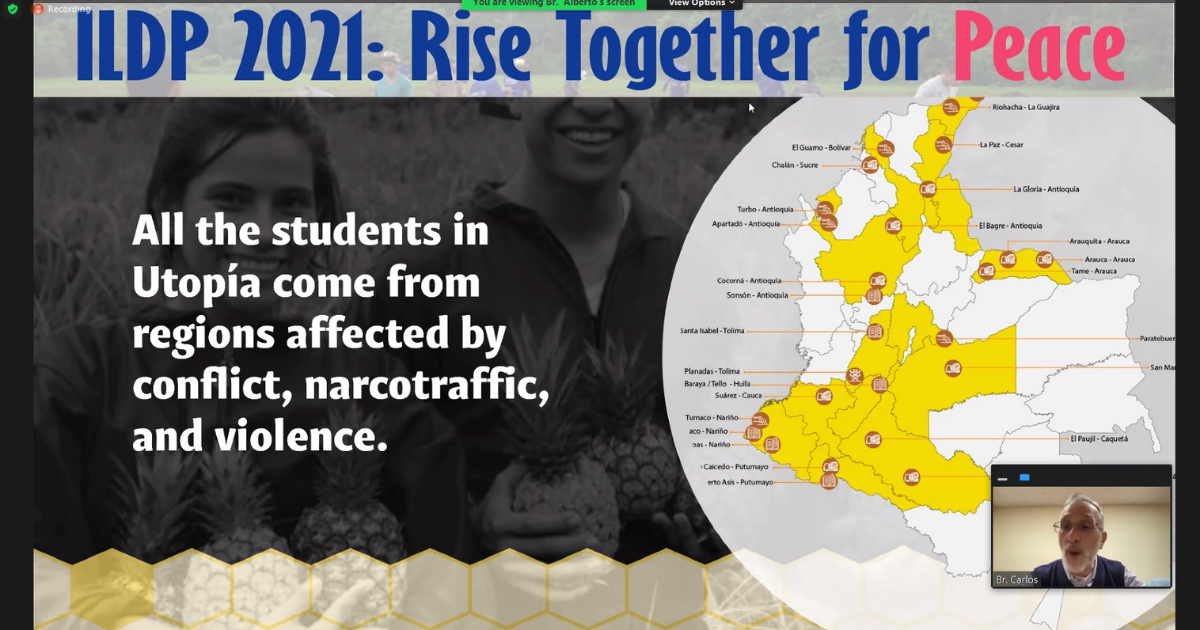

The Utopia program trains young people in Colombia, those with limited economic resources and whose areas have been affected disproportionately by violence and poverty, to become agricultural engineers and community leaders. Students like Calderon are selected through a competitive process. (He described having to travel more than five hours to sit for an entry test.)

After acceptance into Utopia, and over the ensuing three years, students receive a holistic education aimed at professional and personal formation in Lasallian values and developing sustainable agricultural production. They graduate and return to their respective towns as professionals who will carry out projects with the capacity to transform their country and communities.

“Now, I can say I’m a role model for my community,” Calderon said.

He described several key projects that were born of Utopia. One is a reforestation that involves nearly 1,500 families working with Colombia’s state government to transition land usage toward legal crops.

“Those who possess the land don’t always make it productive,” said Br. Carlos Gomez-Restrepo, FSC, the former president of Universidad de La Salle in Bogota, where he helped establish Utopia. The program addresses “the need to build peace in Colombia,” he said, calling rural education “a disaster. I don’t know another way to say it.”

“We need to protect our young people from temptations of warfare, and illegal and illicit activity. Utopia is a drop of water in the ocean, but it is offering educational opportunity to people where there wasn’t opportunity before.”

First introduced in 2010, and educating Colombian youth for more than a decade, Utopia is considered “a premier example of peacebuilding to integrate horizontal efforts for peace at the grassroots level with vertical dimensions of civic and governmental power—an integration necessary for stable peace,” said event moderator Br. Ernest J. Miller, FSC, D.Min., Vice President of Mission, Diversity, and Inclusion.

“Across 341 years of a living tradition of Lasallian education, there has been an evolution of Lasallian education. What is happening in Colombia is a commitment of Lasallian education to peacebuilding.”

—Christopher A. Vito