La Salle University

First Week of Lent Reflection

Looking at the art:

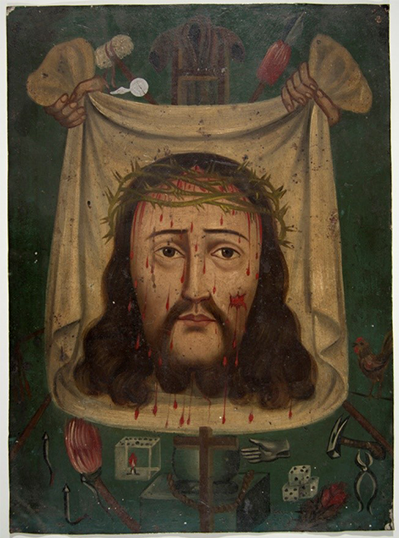

Retablo Painting of Christ with Passion Symbols

19th Century

14 x 10 1/4 in. (36 x 26 cm)

Unknown, Peruvian

Object Type: PAINTINGS

Creation Place: South America, Peru

Medium and Support: Oil on tin

Accession Number: 17-P-600

Current Location: Art Museum : Main Hallway

This painting is a retablo, originally meant to be placed behind the altar in medieval churches, but by the late Middle Ages it referred to any painted devotional work associated with an altar. By the nineteenth century, the face of Jesus had become a staple in Central and South American devotional art intended to portray the sufferings Jesus endured.

In this piece, we see a painting of a painting, evoking the tradition of the bloody face of Jesus imprinted on Veronica’s veil when she wiped his face as he stopped on his way carrying the cross to Golgotha. There is no narrative, no story, no sequence of events, just a static display, a “snapshot,” of what the torture did to Jesus’s face. Instead of narrating the story of how the revered face of Jesus got to this state, the artist clips pieces of the story and scatters them around the face.

It is up to the viewer to engage in the Passion narrative and reconstruct the story. Can you identify the items recounted in the familiar Passion story? Among the symbols of the passion are the crown of thorns on the head of Jesus; a whip at the base of the column where Jesus was flogged; dice to determine which soldier would take his garment; the garment itself above the veil; a sponge on a stick soaked in vinegar mocking Jesus when he said he was thirsty; the bloody spear that pierced his side; the cock that crowed when Peter denied Jesus; the lantern and torch that lighted the way to the place where Jesus was betrayed and arrested; the hand that struck Jesus’s face; hammer, nails and pincers; the cross itself.

Devotional paintings like this derive from the European Counter Reformational aesthetic of engaging emotions to instruct the faithful and convert unbelievers by holding up for view scenes from the gospels. Here two hands hold up the veil showing Jesus’s face to instruct South American Incas, probably Peruvian, during the post Spanish conquest era.

Reflection

This image evokes memories of my childhood. Raised in a Polish neighborhood, the triduum was a time of great drama and emotion. Holy Thursday saw a statue of the scourged Christ in the sanctuary. Gory would be an understatement; pieces of flesh hung off of the body from the scourging. Good Friday’s cross was as bloody. As a small child, my mother would take me to church after the services to venerate the cross and visit the grave. After kneeling down to kiss the cross we went to the grave where a life-sized statue of the dead Christ was the focal point of Good Friday evening and Holy Saturday. I remember staying close to my mother as she would tell me to look at the cross and the dead Christ and remind me of how much Jesus had suffered for me. In similar fashion the image we are looking at has the instruments of torture and death displayed along with Veronica’s veil. The instruments of the Passion are meant to evoke the emotion of the terrible physical suffering that Jesus endured. All of this stands in sharp contrast to the Passion narratives themselves. The evangelists simply state that “Pilate had him scourged” and “when they arrived at the place called Golgotha, they crucified him.” No gory details. Rather than the physical passion the evangelist wants to focus our attention on other aspects of the passion.

These instruments of crucifixion, however, are accompanied by Veronica’s veil or, as the icon is called in Greek, “the image not made by hand.” An image of something that tradition claims is a gift to a woman who provided an act of kindness to Christ on his way to die; an image of someone who is not just human but also divine. Again, there is no reference to Veronica or her veil in the Passion narratives.

So why does this unknown Peruvian artist focus our attention on things and images that the gospel writers do not. What is it about his need for showing the instruments of crucifixion, or my mother’s devout appreciation of the blood and gore of the passion? Maybe it is our need to know, to understand, what this event is all about, our need to understand in concrete ways what happened? Maybe paying attention to the physical passion is out of fear of not wanting to go where the evangelist are trying to lead us; to understand the total abandonment and desolation that Jesus faced. The instruments of the passion, as gory as they are, are easier to handle than the darkness that Jesus faced on the cross. But the artist does not let us forget that Jesus is divine, the beloved of God, who is facing all of this.

This Lent what will I come to understand about the death of Jesus that I had not understood before. How will my prayer lead me along the path of the evangelists? Will I be able, with them, to follow the abandoned Jesus or will I stay on the periphery where, as gory as it is, I can take some comfort in what I know and not be challenged to enter fully into the mystery of the god become human and his saving death.