La Salle University

Third Week of Lent Reflection

Looking at the art:

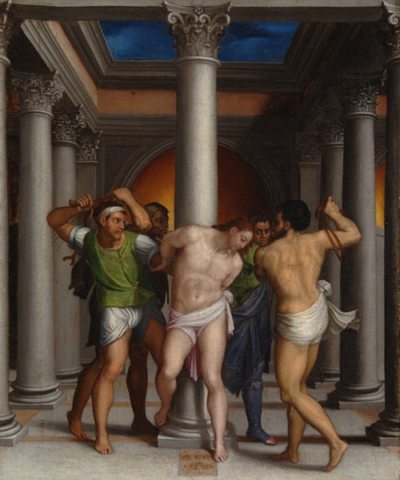

Christ at the Column

1552

16th Century

17 x 14 in. (43.2 x 35.6 cm)

Marcello Venusti, Italian, (c. 1512–1579)

Object Type: PAINTINGS

Creation Place: Europe, Italy

Medium and Support: Oil on canvas

Credit Line: Purchased with funds provided by Benjamin D. Bernstein

Accession Number: 89-P-356

Current Location: Art Museum : 15-16 C Gallery

At first view we are stuck by bodies and columns. The bodies are contorted and in motion; the columns are straight and still. What is happening here? This painting depicts what three of the four gospels report simply as Pilate having Jesus flogged. Reports of Roman flagellation indicate that the victim is bound to a pillar and whipped.

Venusti has organized a symmetrical composition with Jesus tied to a pillar in the foreground center, thus dividing the canvas in half. On each side of Jesus two of Pilate’s men stand with their whips ready to flog him. Again, on each side three other columns recede into the background providing an architectural frame with Jesus and his column in the center. Notice that we see no lashes on Jesus’s body, nor do we see any blood, as is almost always portrayed in scenes of the scourging. Perhaps the first lashes have not yet been inflicted as Pilate’s men raise their whips, their action arrested.

The symmetry of the composition is accentuated by the illusion of a third dimension of depth on this two-dimensional canvas. Venusti accomplishes this by using the then hundred-year-old device of linear perspective. The three pillars on each side recede in size into the background, and the line markings under the pillars converge at an undetermined vanishing point in the dark horizon behind Jesus’s central pillar. This device also guides our eye along the columns to the curved arch in the background and the contrasting angular skylight above. While the background is dark, the foreground is lighted. Overall, this painting is a study in symmetry and contrast. The same ray of light that shines on the central column also shines onto the body of Jesus, thus highlighting the contrast between the straight solid surface of the column and the contorted flesh of Jesus’s body which is now identified with his column. It is almost as if Jesus’s body, sculpted looking and without scars, is an unadulterated statue about to be defiled and broken.

Reflection

We have here a very stylized scourging with none of the blood that we would have imagined. Maybe the scourging is about to begin. Scourging, crowning with thorns, carrying the cross are all part of one narrative and it can be problematic taking them apart. I have seen writers say that the scourging was in reparation for all the sexual sins that would be committed. For me that paints an unappealing view of God: scourging for the sexual sins, crown of thorn of all the murders, etc. This posits a God who wants payment for humanity’s fall from grace. God’s anger, in Anselm’s view, needs to be satisfied.

I see this differently. The Crucifixion is God’s act of profound love. The Crucifixion is Jesus making all of humanity right with God. Paul tells us repeatedly that the death of Jesus saved us according to the scriptures. Scripturally, sin is stepping out of relationship with God. While the moral code is part of that, it is not the driving force. The passion of Jesus, from the garden to his final word is about putting all of creation into right relationship with God. What Jesus does in the Crucifixion is take on himself all the sin of the world and transform it. Jesus takes the hatred and turns it into unconditional love, the loneliness and rejection into acceptance and community, the pain into joy. The death of Jesus makes the relationship between God and humanity whole again. What happened in the Garden of Eden when humanity stepped away from God being the center of everything is put back into place. God is again the center of all creation. Because of that we are saved and because God is at the center there is a way we need to be in the world, with each other and with all of creation. Because of the death of Jesus humanity, creation, will never be separated from the love of God again.

So, while it may be helpful for us personally to focus on separate parts of the passion, those who pray the rosary do it all the time, it is the totality of Jesus’s self-giving that we need to never forget. Do I understand that the death of Jesus, no matter what I do, has put me in right relationship with God? What does that mean for me? What does it mean for the kind of person I am, will be?